Canada’s labour movement came into its own at the turn of the century, and with it, a new breed of Canadian activist emerged: advocates for worker’s rights.

Among them was Helen Jury Armstrong, a vocal proponent for union causes, an ardent feminist and a steadfast anti-war activist.

Unrest in the prairies

In 1919, a perfect storm is brewing on the Canadian prairies. Thousands of demobilized soldiers are returning home after the First World War; at the same time, factories producing for war industries are shutting down. Unemployment is skyrocketing, while bosses are using the sudden surge in the size of the labour pool to keep wages down. The cost of living is 64 per cent higher than it was six years earlier.

Something’s got to give.

On May 1, 1919, the various unions representing Winnipeg’s metal and building trade workers go on strike for the right to form an umbrella union, and therefore gain stronger collective bargaining rights.

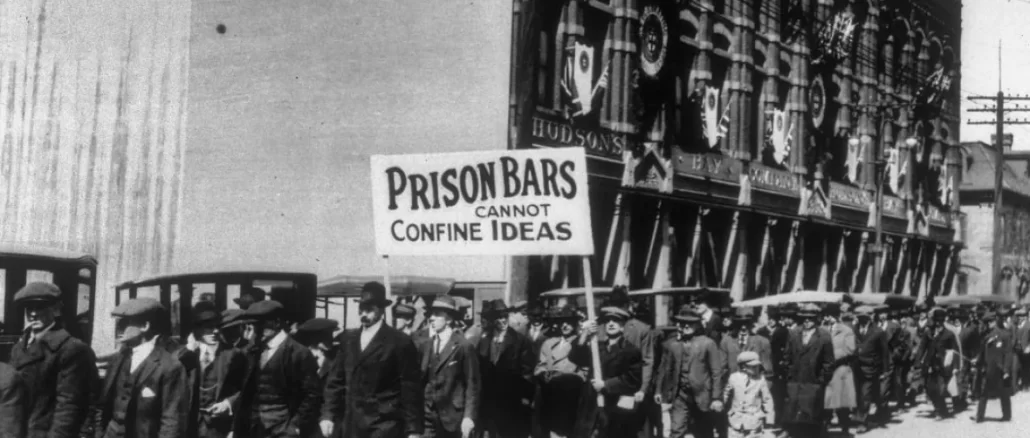

Two weeks later, labour leaders from other unions propose a general strike in solidarity with the metal and building workers. Among them are the telephone operators (also know as “Hello Girls”). By 11 a.m. on May 15, roughly 30,000 workers have walked off the job.

About 10 per cent of them are women, who come mostly from commercial bakeries, confectioners and garment manufacturers. These women have their own issues—most notably, equal pay for equal work—and their own leader, Helen Jury Armstrong.

Activism in the family

Helen Jury Armstrong was born in Toronto in 1875, the eldest of 10 children. Her father, Alfred Jury, was a tailor and a member of The Knights of Labour, an organization that campaigned for the nine-hour work day.

Armstrong began working in her father’s shop at an early age. She would watch as labour leaders, trade unionists, socialists and other advocates for working people came into the shop to discuss and debate with Alfred. Helen ultimately married one of these rabble rousers, a young carpenter named George Armstrong. Wed in 1897, they had three daughters and one son, and spent a few years in New York before heading back to Canada. They settle in Winnipeg, a hotbed of union activism.

Learning to fight

In 1917, Armstrong takes a job at the Labour Temple and is given the task of rejuvenating the dormant Women’s Labour League (WLL). She takes on the role with gusto, leading the clerks at Woolworth’s out on strike that same year.

Against the advice of more moderate, middle class members of the WLL, Armstrong vocally opposes conscription (the practice of ordering people by law to serve in the armed forces).

She brings food and clothes to Stony Mountain Prison, where young men who refuse to serve are locked up for two-year sentences. She agitates on behalf of people who are interned as enemy aliens. Her anti-war work gets her arrested, but also establishes her as a voice on the far left of the movement. She becomes the only woman on the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council.

At a time when female workers make half of what their male counterparts do, she leads the charge for a minimum wage for women. In a letter to the Winnipeg Telegraph, she writes “Girls have got to learn to fight as men have had to do for the right to live, and we women of the Labor League are spending all our spare time in trying to get girls to organize as the master class have done to protect their own interests.”

The Winnipeg General Strike

When the workers walk off the job in 1919, Armstrong is a vital part of the strike effort. She takes deputations from women workers. She helps set up a soup kitchen to feed striker’s families. And she goes to jail. Three times. Once for leading a group of women in shouting down strike-breaking newspaper sellers; twice more for her own disorderly conduct. The anti-strike Citizen newspaper describes her as a “female bolshevicki.”

In 1920, George Armstrong is sent to prison for his part in the strike. While incarcerated, he’s elected to the provincial legislature and takes his seat upon his release. He loses his seat in the next election, two years later. In 1923, Helen Armstrong runs for alderman and loses. With both of their political careers stagnating and George struggling to find work as a carpenter (due to his active involvement in the general strike), the family moves to Chicago in 1924. While she and George return to Winnipeg after the 1929 stock market crash, she spends her final years living near her daughter in California, where she died 1947.

In 2001, Armstrong becomes the subject of The Notorious Mrs. Armstrong, a film by Canadian documentarian Paula Kelly, who describes her as “outraged and outrageous” and a source of indestructible optimism.

H/T CBC “Canada: The Story of Us”